Women at sea – past and present, 2011

"Women at sea – past and present"

Neumühlen 3, Pump station No. 69 - Hamburg Wasser

Design and realisation: Barbara-Kathrin Möbius, Hildegund Schuster.

Sponsors: Altona District, Hamburg Wasser. Photo: Hildegund Schuster ©

One of the solid sandstone walls comprising the facade of pump station number 69 has been used by the Hamburg artists Barbara-Kathrin Möbius and Hildegund Schuster for their portrayal of Women at sea. Conveying the physical impression of standing on a stage, the mural is a vividly fantastic combination of pictures from the working world and the history of discrimination..

It is both eyecatcher and braincatcher that really makes you look and think. On the one hand, an increasing number of vocationally trained women can be found on board. On the other hand, women at sea are still far from being generally accepted the world over. Although it is no longer politically correct to say it's unlucky to have women on board, they still face discrimination and prejudice in the maritime environment. Unnerröck an Bord, dat gifft Malheur. (1)

So who is on the painting? All the personnel on board are women. The tanned captain at the helm with her emerald-green sparkling eyes eclipses everyone else (by the way, it is only since 1987 that women have been able to obtain the ship master's certificate in Germany West)(2) ; standing next to her is the ship's officer holding the binoculars, with three stripes on her uniform; at her side is the stewardess, a job women have been doing already since the 19th century as the woman to take care of creature comforts.

And on the far left we see a girl in a sailor suit. Above her the floating imagination bubbles tell of her dream job at sea. There have always been women who have dreamed of going to sea, just like men do. They have all got the seafarer virus, often dreaming about this in early childhood. Their role model: father, uncle, grandfather. To fulfil their dream of becoming a seafarer, in former times women would dress as men to join a ship's crew.

In the middle of the mural we see the nicely rounded cook, presenting a well-filled plate of pretty-eyed fish. Right next to her is a bright pink pig, whose snout cleverly conceals the pump station's pipe socket, epitomising the nasty sailor's yarn of "no women or pigs on board".

There's a strange figure in the background: the careworn cleaner with her obligatory bucket and broom, but also with a mug of coffee for her work break. And on the far right, the nurse, a vital presence on big ships, here as a figurative symbol, injecting Euros into the steamer called "City of Hamburg" for showpiece projects like the Elbphilharmonie. Meanwhile the radio operator above her sends her message: at sea: new telecommunication developments made this job obsolete 10 years ago, although it was very popular among young women once they were allowed to become radio operators in Germany since 1954.

Round the corner, the ship is being polished with monstrous protective goggles. It's a never ending job for man and women: removing rust and touching up the paintwork. The necessary working utensils - white safety helmet and yellow oilskin - are ready and waiting at the opposite western corner. A white lacy petticoat peeps beneath the oilskin. This is an enigmatic combination of protective everyday workwear with a very feminine garment. It illustrates how ships were preserved as a man's world through seafarer superstitions that women (epitomised by the petticoat) on board would bring bad luck.

The mural illustrates the increasingly modern functions that women fulfil on board ships: no longer just for provisions and for cleaning, now they are also qualified to steer and take the helm, that's the message.

A brief flashback in time(3) serves to show how and when women eventually gained access to their dream job.

For centuries, seafaring jobs were reserved exclusively for men. If women were allowed on ships at all, it was only as passengers. But on the often family-owned coastal vessels, every pair of hands was vital. The wives and daughters often worked as cook, helmsman or deck hand.

During the Second World War and in the post-war period, there were isolated cases of women obtaining certificates of nautical competence, but these were only valid with special authorisation from the authorities. It was not until the late 1950s that the statutory restrictions were lifted (due to a lack of male personnel).

During the 1970s, quite a few young women aspired to a seafaring career. The famous Hamburg-based female ship-owner Reederin Lieselotte von Rantzau established an excellent reputation by being the first to encourage young female seafarers. The situation today is that women account for one fifth of the graduates from the Department of Maritime and Logistics Studies at Jade University of Applied Sciences in Elsfleth (near the city of Bremen).

The upshot of it all is that seafarers are associated with a wide range of stereotypes and clichés that are closely related to conventional role models. It is often claimed that women don't have the technical talent or that they lack sufficient competence to take responsibility for a ship. The distinctly male identification figure of the captain, the sea dog, the Jack Tar, is still firmly anchored in culture.

The artistic approach therefore works with this conflict, with disruptions in biography and career choice, with self-doubt.

The mural clearly depicts how far women had to go before they were allowed to work on board, hampered at every turn by exclusion, hindrances and discrimination.

The mural has nothing to do with bright shiny advertising along the lines of "Hey girls, we've made it: we can join the men's world."

Photo: Hildegund Schuster©

This is expressed by the mural's undertones. There's no sentimentality, no lamentation. But the figures come across in part as anti-idols: used, utilised, brooding more about themselves and withdrawing from conventional viewing habits - something the artist Barbara-Kathrin Möbius is known for, and rather strong stuff in a society where it doesn't do to be incommodious.

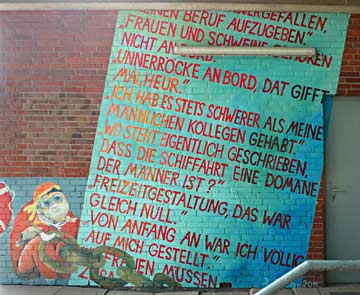

The word strips in matching colours round off the east and west side of the mural, with quotations from the interviews or seafaring expressions. In bright red letters on the east side we read: "I've always had to struggle much more than my male colleagues". "So where does it say that shipping is a men's world?". "We just didn’t have any free time ". "I was completely on my own, right from the start!" „We women just have to stick together."

The words standing out against the bright turquoise background on the west side include: engineer, women at sea, shipping inspector, livelihood, importunate, seasick, merchant shipping, occupational safety, first female captain, low-wage countries, dream job, maiden voyage, late mother, men-shortage..

© Elisabeth von Dücker, 2011

(1) It's unlucky to have women on board.

(2) Many obstacles had to be taken to obtain the necessary exemptions from the authorities before the first ship master's certificates were issued to women.

(3) For details, see: Christine Keitsch: "Women at sea. Female workers on board German merchant shipping since 1945", Flensburg Maritime Museum, 1997

At the inauguration ...

... on 3 August 2011 with around 100 cheerful guests enjoying the wonderful sunshine.

Lots of interested visitors

and beautiful weather at the inauguration

Photo: Ulrike Gay©

In front of the mural from left to right: Hildegund Schuster, Elisabeth von Dücker and Barbara-Kathrin Möbius.

Photo: Ulrike Gay©

Welcome note from our cooperation partner Dr. Christine Keitsch, Director of Brake Maritime Museum to mark the inauguration of the mural:

For more than 20 years now, the "Mural" initiative has been creating a monument to women working in the port and on the high seas.

Everyone involved, the initiators including above all Elisabeth von Dücker, the artists and also the protagonists deserve our absolute esteem and respect for what they have achieved. They have created a refreshingly lively and extremely prevalent presentation of the diversity of the economic role played by women in traditionally male jobs, thus also documenting at the same time the transformation of maritime living and working worlds with increasing numbers of qualified women in skilled roles where they are gradually becoming more accepted.

I am very pleased that we were able to support the current project and hope that the initiative continues to have a lasting effect.